Building boom resumes in as tech firms crave office space

San Franciscans hoping that the city’s five-year, skyline-transforming tech boom is finally cooling off will have to wait a while longer. Maybe a lot longer.

After a six-month period during which it seemed as if demand for tech office space had stalled out, fast-growing companies are once again fanning out across the city in search of space, according to developers and brokerage firms. That has emboldened commercial builders to dust off blueprints and prepare to break ground on office projects that just a few weeks ago seemed likely to be on hold for a while.

“In the last 30 to 60 days, we’ve seen a big uptick in demand for development projects,” said Mike Sanford, executive vice president of Kilroy Realty Corp., which has a 700,000-square-foot project under construction at 1800 Owens St. and a 400,000-square-foot complex queued up at 100 Hooper St. “It’s full-on construction for us.”

A number of factors have converged to boost confidence, according to developers and brokers. The stock market is up near record highs after a short-lived dip caused by the Brexit vote. Investment has bounced back — nationally VC firms invested $15.2 billion into venture-backed startups in the second quarter, up 20.5 percent from $12.7 billion in the first quarter, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers and the National Venture Capital Association.

Tech tenants are in the market for 5.9 million square feet, while biotech firms are looking for 2.5 million square feet, said Steve Richardson, chief operating officer with Alexandria Real Estate Equities, which is constructing headquarters buildings in San Francisco for Pinterest, Stripe and Uber.

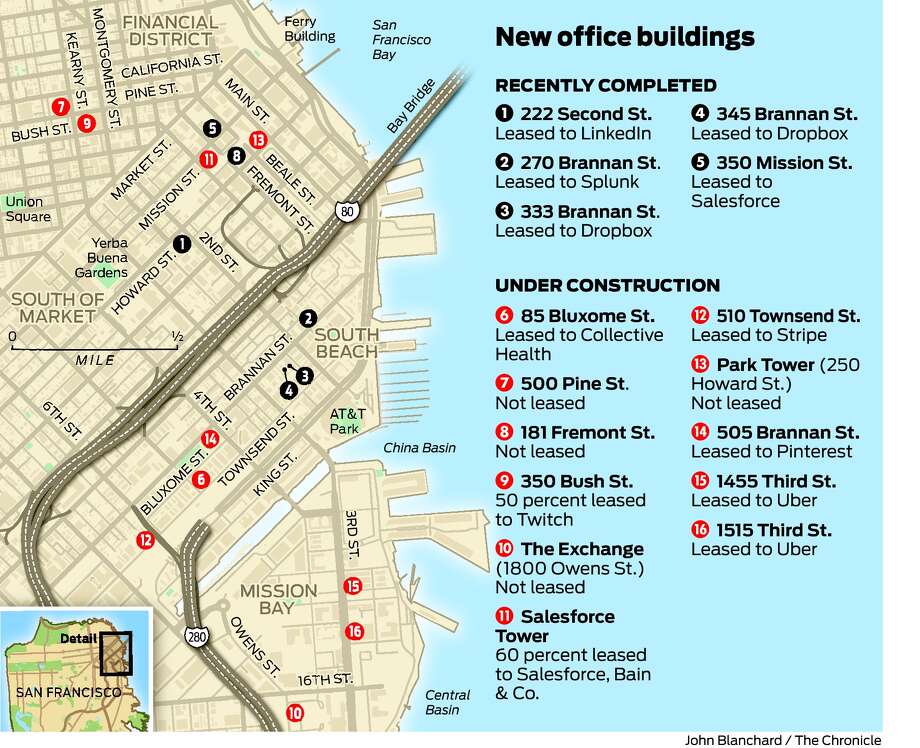

For the army of brokers who make a living attracting tenants to the city’s new glass towers, Exhibit A of the resurgent strength is 350 Bush St., a 19-story tower rising out of the facade of the old Mining Exchange Building. After failing to land a tenant two years into construction, the building has finally gotten its first tenant, the gaming company Twitch, which will take 186,000 square feet.

On the other side of Market Street, the owners of the tower rising at 181 Fremont St. are in advanced talks with the finance website NerdWallet, which has agreed to lease more than 100,000 square feet. And at the Salesforce Tower, which will be San Francisco’s tallest building, 820,000 out of 1.4 million square feet has been leased, and representatives of the developer, Boston Properties, said last week they expect to sign deals on another six to eight floors by the end of the year. In addition to Salesforce, which will occupy half the building, tenants headed to the tower include Bain & Co. and CBRE.

San Francisco has about 5 million square feet of office space under construction, of which roughly half is leased. Kilroy, which has been the most aggressive builder of office space over the past five years, is building a 700,000–square-foot mid-rise complex at 16th and Owens streets at the southwestern corner of Mission Bay. And while no tenants have been announced for the two-building project, Kilroy expects to have a deal signed in the next few months. And as soon as that happens, Kilroy will start construction on the project at Hooper Street.

“Every development under construction and some that are not yet under construction are trading paper with tenants,” said Christopher Roeder of Jones Lang LaSalle, who is part of the leasing team handling Park Tower, under construction at 250 Howard St. “I feel a lot better than I felt 90 days ago.”

Photo: Michael Noble Jr., The Chronicle

But the hot market is not without its downside — what’s good for developers is often painful for tenants. San Francisco office space is the most expensive in the United States — an average of $75 a square foot in the central business district, which has led to the exodus of nonprofits to the East Bay and prompted the financial services firm Charles Schwab to move hundreds of workers to Denver and Dallas.

Colin Yasukochi, research director at CBRE, said rents are high enough that he doesn’t see them rising any more.

Two tenants who were courted by developers of new buildings, Lyft and Fitbit, decided to save money by taking sublease space in buildings being vacated by Dropbox, which moved to two new buildings on Brannan Street, and Charles Schwab, which has been gradually moving workers out of the city for a decade.

“There is demand for blocks of new office space, but there is some resistance to the cost and there is increased scrutiny on the part of tenants,” Yasukochi said. “Since the rental rates have essentially stopped rising, there is not as much urgency on the part of the tenants to transact a deal. Things are moving at a more normal pace than they were in 2013 or 2014.”

Yasukochi said more businesses could leave San Francisco if costs keep rising.

“We need supply to create better balance — the market has been landlord-dominated for many years,” he said. “That is not healthy or sustainable, and that is why rents have been as high as they have been.”

But some relief could be on the way. City planners are putting the final touches on the Central SoMa Plan, which is designed to create millions of square feet of office space and thousands of housing units along the Central Subway route on Fourth Street, which will open in 2019. The plan’s goal is to create enough space for 50,000 workers and 7,500 housing units.

The plan is complicated, however, by Proposition M, the 1986 ballot initiative that aimed to contain the spread of downtown and which limits the amount of new office space that can be approved to 850,000 square feet per year. Currently there are just 500,000 square feet available, with about 8 million square feet of office buildings awaiting approval. That means that office developers seeking to take advantage of the Central SoMa Plan will have to compete against one another for a limited pool of available space.

Planning Director John Rahaim said the Central SoMa Plan, which will probably be up for Board of Supervisors approval in spring of next year, will lay out a vision for decades of ups and downs, booms and busts. Fees from the plan will add $2 billion in public benefits, including affordable housing, manufacturing space, arts space, improved streets and new parks.

“The plan is long-term,” he said. “The plan has always been about accommodating the next phase of job growth. Whether or not the current market warrants it, it’s still the right thing to do in my opinion.”

This article was originally written by J.K. Dineen and appeared here.

Comment (0)