Poseidon Water’s desalination plant in Carlsbad is poised to begin regular operations within days — decades after water officials first considered harvesting drinking water from the sea and 14 years after they formally took the first steps toward its construction.

The opening, to be celebrated with an anticipatory ceremony Monday, will be a milestone for the company, for arid San Diego County and for all of California.

The San Diego region, which imports most of its water, will enter a new era in its quest for a reliable supply of this precious and increasingly pricey commodity. For the first time, a significant portion of its water supply will come from the sea.

Poseidon will sell the fresh water it produces to the San Diego County Water Authority, the region’s main provider. The authority will resell that water to retail districts that serve residents, schools and businesses. The Poseidon plant can create up to 50 million gallons of fresh water a day; that’s about 8 percent to 10 percent of the county’s overall supply.

For California, the Poseidon plant represents the mainstreaming of seawater desalination in California. Ocean desalination has long been used in nations such as Saudi Arabia, Australia and Israel, where the company that designed the Carlsbad plant, Israel Desalination Enterprises, is based. Israel’s extensive use of desalination to conquer a seemingly perpetual drought has become an internationally recognized success story.

California may be poised to join the trend. About 15 other desalination projects have been proposed for the state’s coastline, from the San Francisco Bay Area to Southern California. The figure doesn’t include those in Mexico that would serve San Diego County to varying degrees.

And for Poseidon, successfully operating the largest desalination plant in the Western Hemisphere would demonstrate that large-scale ocean desalination is feasible in California. It could strengthen the company’s case for building a similar facility in Huntington Beach.

While desalination of brackish water has been common, seawater desalination has been mostly confined to niche applications where no other source of water is available, such as on Catalina Island.

Along with other steps that San Diego County officials have taken or hope to take, from buying water from Imperial Valley farmers to potentially recycling wastewater into tap water, ocean desalination could give the region greater control over its water destiny.

That prospect comes at a steep price: Altogether, the undertakings will cost billions of dollars. Business, agricultural and residential water utility customers will bear these expenses.

Water from the Poseidon plant costs about twice as much as water purchased from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, the region’s largest water wholesaler.

Ocean desalination is also more expensive than the drinking water recycled from sewage, from which the city of San Diego plans to get one-third of its drinkable water by 2035. Previous city leaders rejected the option, fearing a public backlash over what some dubbed “toilet to tap.”

San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer — urged on by regulators, environmentalists, the life-sciences industry and others — has decided that the need for water recycling is too great to continue passing it up. He and the City Council last month supported a multi-year increase in water bills partly to pay for expansion of the recycling infrastructure, which is expected to grow from a single-site pilot project to a network of filtration plants, pumps and pipelines.

Critics of the Poseidon plant in Carlsbad said its technology uses enormous amounts of electricity, harms marine life and locks San Diegans into a costly option that they could have avoided entirely. They said for years the region’s elected officials and water managers should have put more stress on everyday conservation while being more aggressive in starting water recycling.

End of the pipeline

San Diego County has always been vulnerable to drought because it has little water of its own and is located at the end of the pipeline for imported water.

This vulnerability didn’t hit home until the late 1980s. Until then, the Metropolitan Water District had proved to be an extremely reliable source of water. In most years, there was an abundance, and in lean years there was still enough to scrape by.

That changed with the severe drought of 1987 to 1992.

By 1991, Metropolitan board members were seriously discussing a proposal to cut water deliveries to its member agencies by 50 percent. Since the agency supplied about 95 percent of the water used in the county, that would have represented a ruinous cutback.

By contrast, the city of Los Angeles was less vulnerable. The city had secured its own municipal supply decades ago from the Owens Valley, and used Metropolitan water as a secondary source.

That 50 percent cut never materialized, thanks to the last-minute storms that produced what went down in history as “Miracle March” in 1991.

The county water authority resolved to get the county out of that vulnerable position by diversifying its supply. This included conserving water and securing supplies from outside Metropolitan. Ocean desalination became part of that mix of options.

The Poseidon plant arose out of two events at the turn of the century. One, Poseidon began a feasibility study in 2000 about building a desalination plant in Carlsbad by the Encina power plant, the location that was ultimately chosen. Two, the San Diego County Water Authority voted in 2001 to spend $50,000 to search for good locations for a desalination plant.

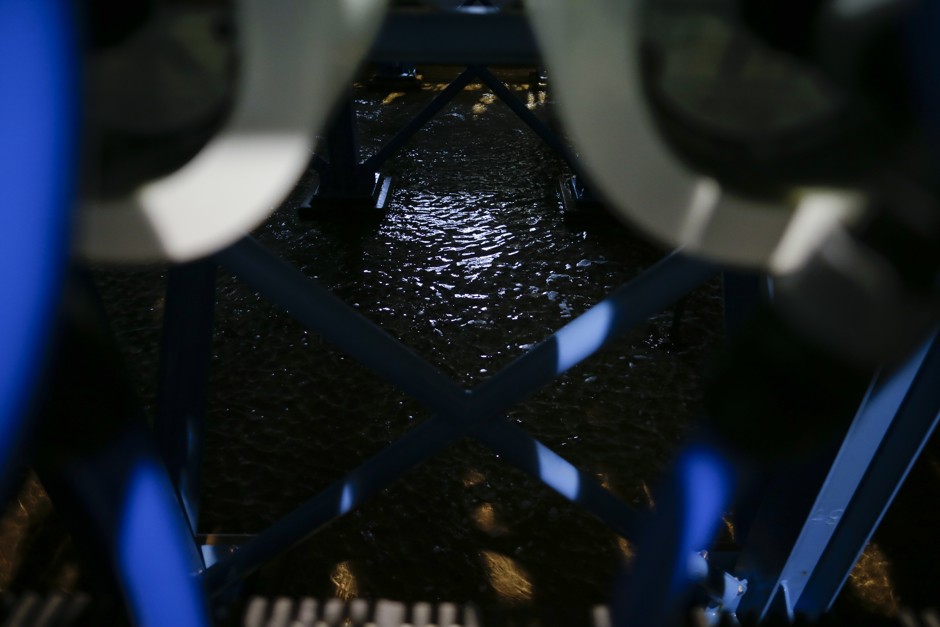

The Carlsbad site had the significant advantage of being able to piggyback on an existing seawater intake and return system, used to cool the power plant. That meant the desalination plant should have less of an environmental impact than at other coastal locations. Moreover, the city of Carlsbad was interested in securing the water.

Then as now, desalination cost more than other sources of water. But the difference had narrowed considerably by 2001.

In 1991, Southern California Edison shut down an experimental seawater desalination plant it built on Catalina Island. The desalted water produced by that facility cost about $3,000 per acre-foot.

In 2001, Poseidon reported having reduced that expense to about $560 per acre-foot, about 7 percent more than the $521 per acre-foot that members of the county water authority paid for water at the time.

An acre-foot is about 326,000 gallons of water — what two average single-family households use in a year.

Busting the budget

In the early 2000s, the Poseidon plant was estimated to cost about $270 million, a figure that rose to $300 million, to $530 million and finally to about $1 billion. One environmentalist critic, Peter Gleick, named it one of the “zombie” water projects that would never get built, but never die.

However, the price for other sources of water also went up, and continued shortages of imported water drove home the desirability of a local source.

Now, 14 years later, the actual cost of Poseidon’s desalination water turned out to be about $2,000 an acre-foot, while water from Metropolitan costs about half that. Plans for the desalination plant were changed, environmental mitigation added in, and energy costs to run the plant also rose.

Years of planning reviews and public hearings lay ahead, along with protests and lawsuits over potential environmental harm, along with a temporary halt to talks between the county water authority and Poseidon in 2006. This was prompted by a decision of the power plant’s owner to replace it with a new facility that didn’t need seawater for cooling. The switch made an environmental impact report based on the earlier assumption no longer valid.

“Please know that this board is fully committed to seawater desalination as an important water supply for the county, but we will no longer pursue such a facility in Carlsbad.,” wrote then-water authority Chairman James Bond in an opinion article in the North County Times. “Rather, we will focus our seawater desalination efforts in other parts of the county and work closely with our member agencies on other local water supply projects.”

At that time, it looked like Poseidon and the city of Carlsbad might conclude their own deal. But Carlsbad by itself lacked the financial heft the county water authority carried, essential for financing the project.

Poseidon pushed ahead, and in 2008 won a critical approval from the California Coastal Commission, which had previously been skeptical of the project. Other good news for Poseidon swiftly followed.

In 2009, the San Diego Regional Water Quality Control Board unanimously approved a permit for the plant, lawsuits against the plant were rejected and various local water agencies signed on to buy water from Poseidon.

However, those agencies struggled to conclude a workable deal, so they asked the county water authority to help. That agency stepped in, and after months of negotiations approved a term sheet setting the general conditions, followed by more negotiations. Final approval came on Nov. 29, 2012.

New environment

The three years since that approval have both confirmed and challenged assumptions that went into the desalination project.

Extended drought has confirmed that San Diego County needs more local sources of water to provide a reliable supply. But now that the water is available, local water agencies may not benefit as they anticipated — at least in the short term.

Under Gov. Jerry Brown’s executive order for the drought, water agencies must cut back an average of 25 percent from residential water use of two years ago. That mandate is strictly based on past usage, and doesn’t take into account any new sources of water that a region may have been able to secure.

The county water authority and other civic leaders said this arrangement is unfair, pointing to the billions of dollars they have spent on water reliability programs during the past 25 years. Those efforts have allowed the region to lower its demand for water from Northern California and the Metropolitan Water District.

Such investments should be recognized with lower conservation targets, the local leaders said.

Brown has given general assurances that he will make adjustments once the existing conservation mandate expires in February.

He hasn’t specified whether San Diego County’s water-reliability programs, including the new supply from the Poseidon facility in Carlsbad, will influence his calculations. And if the much-heralded El Niño storms don’t relieve the drought by January, Brown said he will extend the conservation mandate.

Comment (0)